Climate-related disasters are a global phenomenon. Earlier this year in Colombia, heavy rains overnight caused rivers to burst their banks, taking over 200 lives. In Quebec, Canada, excessive rainfall flooded thousands of homes. But it is Asia and the Pacific that are bearing the brunt. In Sri Lanka’s latest floods, the worst since 2003, rainfall that would have been usual for a year fell in just 24 hours in some places. Landslides are becoming common in many parts of Asia during the monsoon season because uplands have been stripped of forest cover to clear land for export crops.

Locally, disaster risks are increasing because more people are exposed. Higher population densities across developing Asia mean that more people are moving into flood-prone areas. Unregulated urbanization and poor drainage and flood protection are dangerously raising the stakes. The effect of Chennai’s severe monsoon floods of 2015 were made worse by uncontrolled construction over natural flood discharge channels.

Making wrong decisions in disaster flood management can have disastrous consequences. Thailand’s 2011 floods—which submerged economic heartlands and caused losses amounting to 13 percent of GDP—were aggravated by the misjudged release of water from dams. In the 2013 floods in Uttarakhand, India, the debris of the building of dams upstream blocked rivers, augmenting the overflow.

Globally, the connection with global warming is unmistakable, even though scientists are careful not to link any single flood or storm to climate change. Global data over the past 50 years show that the incidence of floods and storms is linked not only to population density and people’s vulnerability to hazards but also to greenhouse gas emissions affecting temperatures and precipitation and generating climate extremes.

Because the rising occurrence of disasters is linked to human action, disaster prevention and risk reduction must become a bigger priority to protect human and physical capital. Governments recognize the increasing incidence of disasters. But climate change implications are still not part of the calculations that help form economic decisions. Or put another way: economists by and large are still projecting economic growth rates that are unaffected by climate scenarios.

Countries are not spending enough on disaster prevention and risk reduction. According to one estimate, this needs to be 1–2 percent of national budgets. A stark example of this under-resourced investment is that for every US$100 of official development assistance, only US$0.40 cents go to disaster risk reduction. Yet acting on disaster prevention makes good economic sense. New York’s disaster preparedness and prevention efforts after Hurricane Sandy in 2012 boosted confidence among investors and businesses, leveraged private investments, and helped stimulate growth.

Importantly, emergency response and disaster relief need top attention, including getting aid to remote areas in time. A neglected aspect is making hospitals, emergency shelters and other vital installations more disaster resistant and ensuring functioning lifelines — notably potable water, first aid and power supplies — during disasters. Readiness also involves care in zoning regulations and building codes to protect businesses, homes and neighborhoods. This is an essential part of risk management as floods can disrupt supply chains and information networks, as we have seen in Sri Lanka, Chennai and Thailand.

But disaster prevention will be futile unless concerted global action is also taken to tackle runaway climate change. Vast differences exist in emissions from countries, and many will need technological and financial support in adapting to climate change. To this end, a $100bn financing plan to support climate adaptation and mitigation is a key component of the landmark Paris climate change agreement of 2015.

Going forward, effective responses to disasters are predicated on global action to mitigate climate change. Leadership of the largest emitters, the United States in per capita terms and China in the aggregate, is crucial, among other things, to encourage others also to take strong action. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s threat to pull out of the Paris agreement, if carried through, would be an assault on global development.

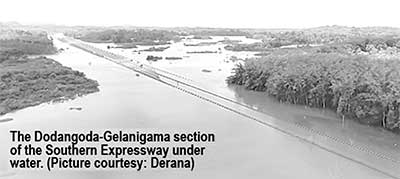

Sri Lanka floods are another stark reminder of the priority that must be accorded to disaster resilience in national development programs. But for these programs to deliver results, climate mitigation and adaption must become integral to disaster resiliency.

Source: The Island | 29 May 2017