Rich countries have promised to mobilize $100bn a year by 2020 in climate finance for poor countries, and they remain well short of their target even though a number of key nations such as the UK, China and France have upped their funding pledges in recent weeks.

But the total amount of investment required for the climate mitigation and adaptation measures necessary to limit average global temperature increases to less than 2C far exceeds the internationally-agreed climate finance goal. More than $6tr annual investment is required for new low carbon infrastructure each year, according to The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, while the UN's Environment Programme (UNEP) reckons a further $150bn a year needed by 2025 to help boost the climate resilience of existing infrastructure.

Countries have consistently argued there is no chance that all, or even most of this money will come from governments, so emerging financing models are slowly gathering pace to encourage the private sector to step in and bridge the gap.

Green bonds are fast becoming one of the most popular mechanisms for allowing investors to directly back low carbon and climate change adaptation projects, with issuance expected to reach $60bn to $70bn this year. A recent report by the Climate Bonds Initiative, UNEP, and The World Bank predicted that with the right support in place, $1tr of green bonds could be issued a year by 2020, plugging a large chunk of the climate finance gap.

But the nascent market still faces a number of challenges, with investors unsure about what they should be looking for when investing in green bonds.

BusinessGreen has spoken to a number of leading responsible investors to help guide those interested in joining the green bond market.

What is a green bond?

So what exactly is a green bond and how do you know if you are investing in one? At their simplest, it is a "climate themed" bond - an IOU from a government, bank or institution looking to raise money to invest in climate-related projects.

But as the market has grown attempts have been made to set standards and help investors be sure their money really is helping to tackle climate change.

The Climate Bonds Initiative has a certified green bond scheme that is designed to make it easier for pension trustees and smaller investors to choose investment products wisely.

These officially labelled green bonds try to guarantee the proceeds will directly pay for a low carbon infrastructure or climate adaptation projects, such as renewable energy development or flood resilience measures.

The officially labelled green bond market stood at $66bn this summer and is growing at a rapid rate, but it remains relatively small compared to the unofficial climate-aligned bond market which is worth $532bn a year.

The standard is a good starting point and brings some certainty for investors, but many people may have more questions.

For example, some investors may feel uncomfortable about an oil giant issuing a green bond that promises to invest in solar panels. They may deem it hypocritical for a company that makes the vast majority of its profits from contributing to climate change to now be seeking to raise money for low carbon alternatives.

Similarly, a company which is broadly considered green in its activities does not automatically qualify for the label when it issues bonds - they have to prove the money will be funding climate measures.

Investors remain split on these issues. For example, Manuel Lewin, head of responsible investment at Zurich, says it is crucial for these more controversial companies to issue green bonds as a way of helping to raise awareness of the emerging market. "If the green market was only the green poster children and only the window solar companies would issue green bonds, I don't think it would make a big difference," he warns. "The very fact that green bonds can be appealing to banks and oil companies - that's what really makes a difference."

He argues the green bonds market needs to find a way to welcome low bonds from high carbon companies. "We would like to see more companies come to market - those companies that are a bit more controversial and where you need to think a little bit harder about whether we're going to be comfortable with that," he says. "But the market needs that, I think this is a good thing."

As well as using the green bond label, Zurich assesses each green bond on its own merits. With the market still in its early stages, standards are ill-defined and investment is very much done on a case-by-case basis, says Lewin.

As much as possible, Zurich will engage in "active dialogue" with the issuer from an early stage to understand exactly how the bond is designed to work. This is a crucial part of the process, and could also allow Zurich to influence the deal.

"Transparency is the most important thing in this market," Lewin says. "It's not realistic for there to be a single and absolute standard that will define what is green and what is not. So in the absence of that, it's really important that as investors, we have transparency to make up our own minds."

Are green bonds investing where they should be?

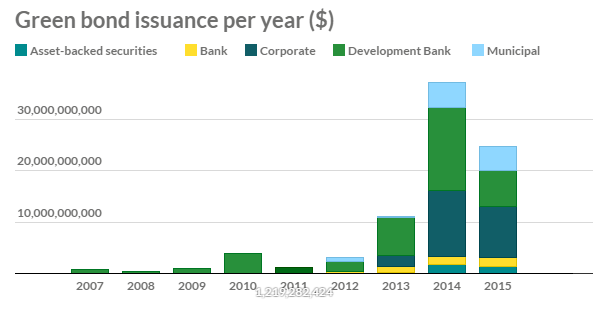

Back in 2011, when the green bond market was tiny, development banks such as the World Bank were the only issuers on the scene so it was relatively easy for investors to assess the credibility of the bond.

But as the market has grown, so too has the range of issuers. This year the biggest proportion of issuers so far has been corporates, while banks and cities have also taken a slice of the market share.

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative - data up to September 2015

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative - data up to September 2015

So transparency remains a key concern. Investors should look for a clear and measurable mandate from the issuer on how they plan to invest their money, and then find out how often the issuer plans to report back.

Damian Regan, a director in risk assurance services at consultancy PwC, says investors should be looking for commitment from the issuer to provide assurance on a yearly basis.

"When people typically buy a bond all they're interested in is the coupon and they're not really worried where that money goes," he says. "But as soon as you put a green wrap around it then you've got a reason for investing in it. Therefore, whether you hit that mandate becomes critical to the investor. There's no financial loss to the investor, but they would feel hard done by if they invested in something that purported to be green but wasn't."

What's the impact?

As well as ensuring the money went where the issuer promised, you should also seek to find out if the bond had the desired climate impact. In short, did it deliver on the greenhouse gas reductions that it promised?

Again, those looking to purchase green bonds should be looking for a clear goal from the issuer of what they are hoping to achieve and a timetable for reporting back on progress, says Regan.

Zurich's Lewin says to ensure they are getting what they paid for, his team regularly check in with the issuer - the conversation doesn't just end once the investment has been made.

With the market still in early stages, it's difficult to know how many green bond issuers have failed to deliver on their pledges. But this is probably because some investors are not providing a clear enough mandate at the start, allowing them to then claim they have delivered on promises that were too vague to begin with.

The emergence of the green bond market is opening up a raft of opportunities for companies to combine their investment and environmental expertise to tackle one of the world's biggest challenges. Those companies that lead the emergence of this important new market could find themselves benefiting in the long term both on a financial and reputational level, but only if they embrace the safeguards necessary to ensure green bonds are truly green.

This article is part of BusinessGreen's Road to Paris hub, hosted in association with PwC

Source: Business Green | 19 October 2015